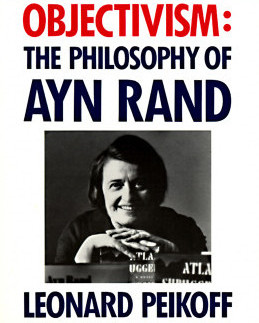

An excerpt from chapter 1 on Reality from Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand by Leonard Peikoff.

After a child has observed a number of causal sequences, and thereby come to view existence (implicitly) as an orderly, predictable realm, he has advanced enough to gain his first inkling of his own faculty of cognition. This occurs when he discovers causal sequences involving his own senses. For example, he discovers that when he closes his eyes the (visual) world disappears, and that it reappears when he opens them. This kind of experience is the child’s first grasp of his own means of perception, and thus of the inner world as against the outer, or the subject of cognition as against the object. It is his implicit grasp of the last of the three basic axiomatic concepts, the concept of “consciousness.”

From the outset, consciousness presents itself as something specific—as a faculty of perceiving an object, not of creating or changing it. For instance, a child may hate the food set in front of him and refuse even to look at it. But his inner state does not erase his dinner. Leaving aside physical action, the food is impervious; it is unaffected by a process of consciousness as such. It is unaffected by anyone’s perception or nonperception, memory or fantasy, desire or fury—just as a book refuses to roll despite anyone’s tantrums, or a pillow to rattle, or a block to float.

The basic fact implicit in such observations is that consciousness, like every other kind of entity, acts in a certain way and only in that way. In adult, philosophic terms, we refer to this fact as the “primacy of existence,” a principle that is fundamental to the metaphysics of Objectivism.

Existence, this principle declares, …

Read the rest in Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand.